[ad_1]

What does it mean to be an American company?

Recently, U.S. Trade Representative Ambassador Tai questioned whether being headquartered in the U.S. is sufficient for a company to be American or whether policymakers should also consider where companies pay taxes.

Her logic suggests that if a company is headquartered in the United States but primarily pays taxes to other governments because of its international footprint, then U.S. trade policy should focus less on protecting its interests.

This thinking is faulty for three reasons. First, large companies headquartered in the U.S. pay the bulk of their taxes to the U.S. government. Second, U.S. negotiators have agreed to rules that will reduce the amount of taxes some multinationals will pay to the U.S. and increase the amount those companies pay abroad. Third, other countries are targeting U.S. companies with discriminatory policies and the U.S. approach to digital taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

and trade will impact where U.S. companies owe taxes.

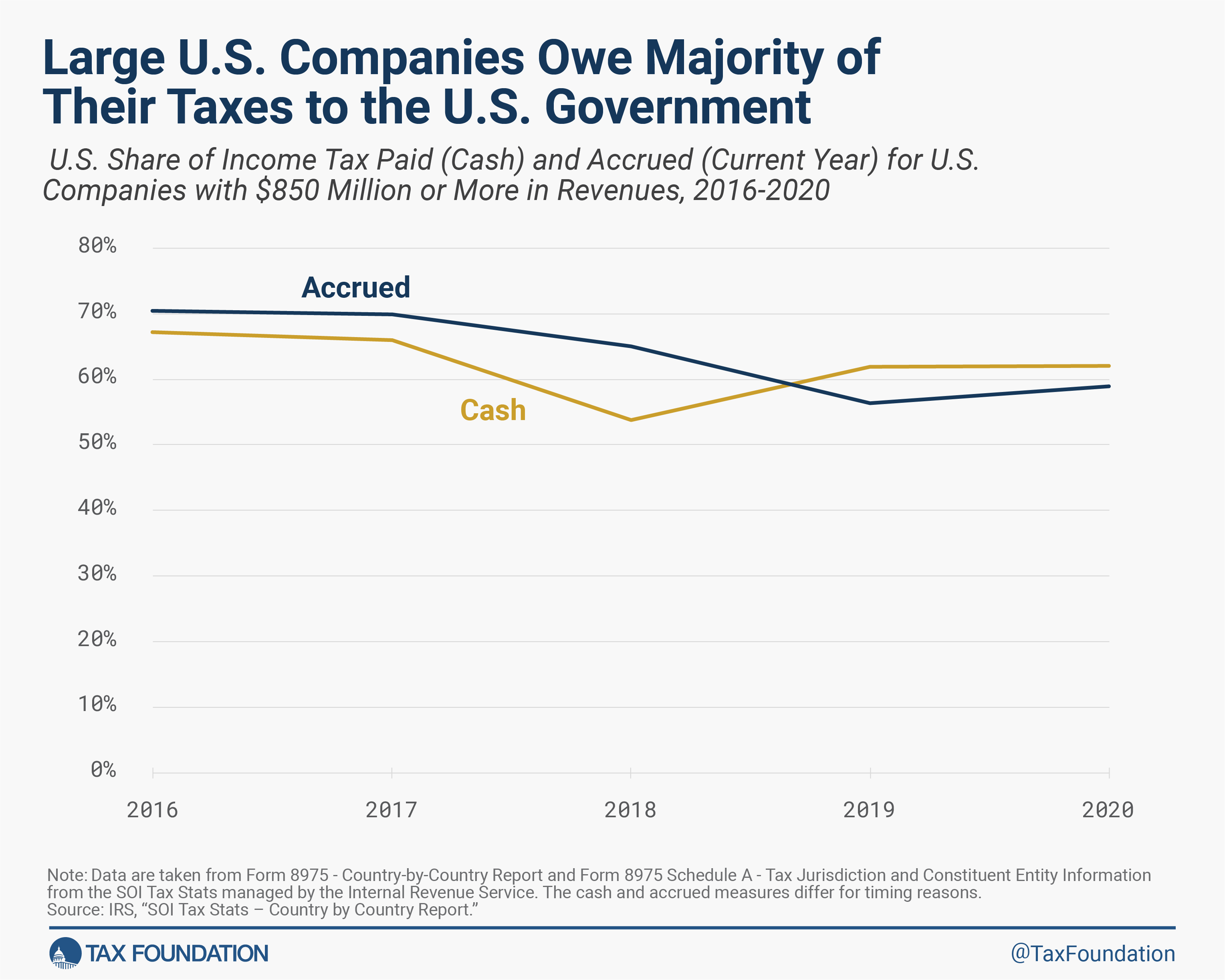

The Internal Revenue Service collects data each year on where U.S. companies with more than $850 million in revenue pay taxes. These country-by-country reports show that on both a cash and accrual basis, the U.S. share of taxes owed by these companies was north of 50 percent each year from 2016 to 2020. In 2020, U.S. companies reported income tax paid on a cash basis of $311 billion in total, with $193 billion—or 62 percent—going to the U.S. The second-largest jurisdiction receiving U.S. companies’ tax dollars was the United Kingdom, which took in $13 billion—or 4 percent.

This trend holds even for digital companies, which Ambassador Tai mentioned specifically. Digitalized business models can be found in just about any industry these days, but information and services are two key areas where they have become particularly dominant.

Information companies paid or owed about 71 percent of their taxes to the U.S. government on average between 2019 and 2020. In 2020, information companies paid $44 billion in taxes (cash basis), of which $30 billion (68 percent) was paid to the U.S. Ireland came in second with U.S. information companies paying $5 billion (11 percent) in taxes there.

On average between 2019 and 2020, professional services owed about half of their taxes to the U.S. In 2020, the U.S. was the top jurisdiction for cash tax payments, making up $4 billion out of $8 billion in total (50 percent), and the United Kingdom came in second with $500 million (6 percent) in cash tax payments.

Next, under President Biden, the U.S. has taken steps to have our multinationals pay fewer taxes in the U.S. and more taxes abroad. This year marks the beginning of a new global minimum tax, spearheaded by the OECD with support from the U.S. Treasury, to ensure multinational companies “pay their fair share.” Of its many features, the global minimum tax fundamentally increases the foreign tax burden of U.S.-based companies while decreasing the amount of domestic tax owned. But if “taxes paid at home versus abroad” is the metric the Biden administration wants to use to determine a company’s Americanness, then many companies that do business across borders could soon cease to be considered American under the new minimum tax.

Moreover, Ambassador Tai’s comments neglect to acknowledge the threat U.S. businesses face from other jurisdictions around the world, including digital services taxes (most commonly found in Europe), equalization levies, and other policies primarily targeted at U.S. companies. By design, these taxes discriminate against large U.S. digital companies and increase the amount of taxes U.S. companies pay to other jurisdictions.

Ambassador Tai is right to wonder what defines an American company from a tax perspective. Until the 2017 tax reforms, U.S. policies practically encouraged companies to avoid being headquartered in the U.S. But the premise of her question is faulty; U.S. multinational companies pay a significant share of their taxes to the U.S. government. And if taxes paid to the United States is the ambassador’s chosen metric, then policies like the global minimum tax and digital services taxes run contrary to that.

A smarter approach is to continue building on the 2017 tax reforms—which significantly reduced incentives for inversions. By making some of its temporary features—like full expensingFull expensing allows businesses to immediately deduct the full cost of certain investments in new or improved technology, equipment, or buildings. It alleviates a bias in the tax code and incentivizes companies to invest more, which, in the long run, raises worker productivity, boosts wages, and creates more jobs.

—permanent, while also working to roll back the tariffs put in place under the previous administration, U.S. policymakers could help companies that started, grew, and have succeeded in America continue to do so here.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Share

[ad_2]

Source link