[ad_1]

Note: The following is the written testimony of Sean Bray, Director of European Policy at the TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

Foundation, prepared for a hearing before the European Parliament Subcommittee on Tax Matters (FISC) on January 23, 2024, titled, “Capital Gains Taxation in the EU.”

Dear Chair Tang and Distinguished Members of the FISC Committee,

Thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony on capital gains taxation in the EU.

Across EU Member States, tax rates on capital gains average 18.6 percent, though they vary widely. Denmark charges the highest top rate of 42 percent rate. Finland and France charge 34 percent, while Bulgaria and Romania charge 10 percent. Meanwhile, five Member States, including Belgium, Czechia, Luxembourg, Slovakia, and Slovenia, have a zero percent rate under various conditions.

The theme of this hearing is the harm that non-harmonized capital gains rates can cause in the EU. Presumably, some will argue that the harm is coming from those five Member States with zero percent rates. Others may also argue that it is unfair to have lower tax rates on capital gains than on labor income and offer dubious political motivations for why such variations exist in the first place. These arguments do not tell the whole story.

Frankly, I agree that disparate capital gains rates can cause harm to the European economy, and there is a question of fairness to discuss. However, it is countries with higher rates, not lower rates, that are causing the most harm. Furthermore, capital gains should be considered alongside the corporate income taxA corporate income tax (CIT) is levied by federal and state governments on business profits. Many companies are not subject to the CIT because they are taxed as pass-through businesses, with income reportable under the individual income tax.

. Without the broader picture, it is misleading to focus only on the capital gains rates in those five Member States.

A Double Tax on Corporate Income

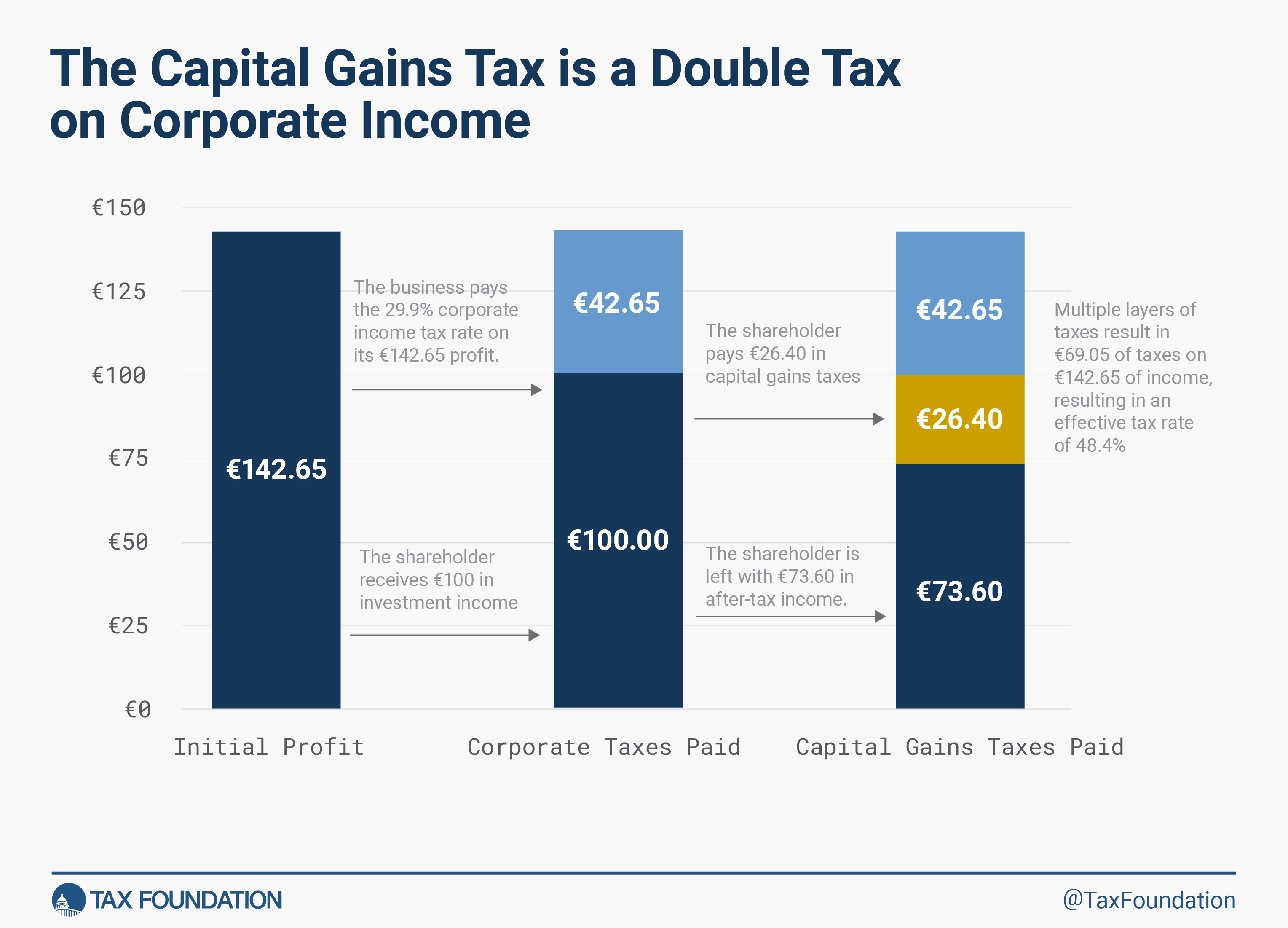

To start, it is essential to understand that the taxation of capital gains places a double tax on corporate income. Ideally, under a neutral tax system, each euro of income would only be taxed once. However, this is not the case, as capital gains face multiple layers of tax.

Before shareholders pay taxes, the business pays the corporate income tax on its profits. Therefore, when the shareholder pays their layer of tax at the personal level, they are doing so on capital gains distributed from after-tax profits.[1]

For example, Figure 1 below shows the double tax burden on income in Germany, which faces a 29.9 percent statutory corporate income tax rate and a 26.4 percent capital gains rate.

This means that, even in Member States with a zero percent capital gains rate, this income is still being taxed by the corporate income tax. To compensate for this double layer of taxation, governments generally charge a lower tax rate on capital gains than ordinary income.

The tax rate that incorporates the capital gains rate plus the corporate income rate is called the integrated tax rate on corporate income. This rate is more indicative of the real-world economic impact of capital gains taxation than the simple capital gains rate.

Table 1 shows that the average integrated tax rate is much higher than the average capital gains rate. Ironically, it also shows that corporate income in Belgium (a country with a zero percent capital gains rate), faces a higher integrated rate than multiple Member States with non-zero capital gains rates.

Another economic rationale for charging a lower rate is that most Member States do not adjust gains for inflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power.

. This means that investors can be taxed on capital gains that accrue due to price-level increases rather than real gains.[2]

Importance of Saving and EU Capital Markets Union

Generally, higher capital gains taxes create a bias against saving and investment, reduce capital formation, and slow economic growth.[3] Capital gains taxes distort the decision to immediately consume or save over time because there is an additional tax burden on saving.

These taxes can be especially harmful to entrepreneurship and small businesses that require capital. The EU cannot afford this given its aging demographic and declining long-term growth projects.

Furthermore, if the integrated rate on corporate income is high and interest is deductible, then the balance toward debt financing will be relatively strong.[4] Businesses will be more likely to finance their investments through debt rather than equity, with fewer IPOs and private offerings.[5] This would be yet another hindrance to achieving a vibrant EU Capital Markets Union.

Conclusion

Some may argue that capital gains rates in the EU should be harmonized to a rate up to 40 percent higher than the status quo. This would harm the European economy.

Instead, policymakers should look for principled ways to increase saving, investment, and economic growth. If a harmonized EU capital gains rate of zero percent makes politicians uncomfortable, then the second-best policy option would be to at least encourage long-term investment and saving with a zero percent long-term capital gains rate.

Thank you again for the opportunity to testify here today, and I look forward to your questions.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

[1] Erica York, “An Overview of Capital Gains Taxes,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 16, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/capital-gains-taxes/.

[2] Kyle Pomerleau, “How One Can Face an Infinite Effective Tax Rate on Capital Gains,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 7, 2015, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/how-one-can-face-infinite-effective-tax-rate-capital-gains/.

[3] Daniel Bunn and Elke Asen, “Savings and Investment: The Tax Treatment of Stock and Retirement Accounts in the OECD,” Tax Foundation, May 26, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/savings-and-investment-oecd/.

[4] Elke Asen, “Double TaxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income.

of Corporate Income in the United States and the OECD,” Tax Foundation, Jan. 13, 2021, https://taxfoundation.org/data/all/federal/double-taxation-of-corporate-income/#Distortions.

[5] Rudd A. de Mooij, “Tax Biases to Debt Finance: Assessing the Problem, Finding Solutions,” IMF, May 3, 2011, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2011/sdn1111.pdf.

Share

[ad_2]

Source link