[ad_1]

Note: The following is the testimony of Daniel Bunn, President & CEO of TaxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

Foundation, before the U.S. House Ways & Means Subcommittee on Tax hearing on March 7, 2024, titled, “OECD Pillar 1: Ensuring the Biden Administration Puts Americans First”

Chairman Kelly, Ranking Member Thompson, and distinguished members of the Subcommittee on Tax, thank you for the opportunity to testify on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Pillar One project. I am Daniel Bunn, President & CEO of Tax Foundation.

Tax Foundation has monitored the development of Pillar One since its origin five years ago. My appraisal of the project back in 2019 concluded with an assessment of the potential complexities, new uncertainties, and the need to eliminate discriminatory digital services taxes (DSTs).[1]

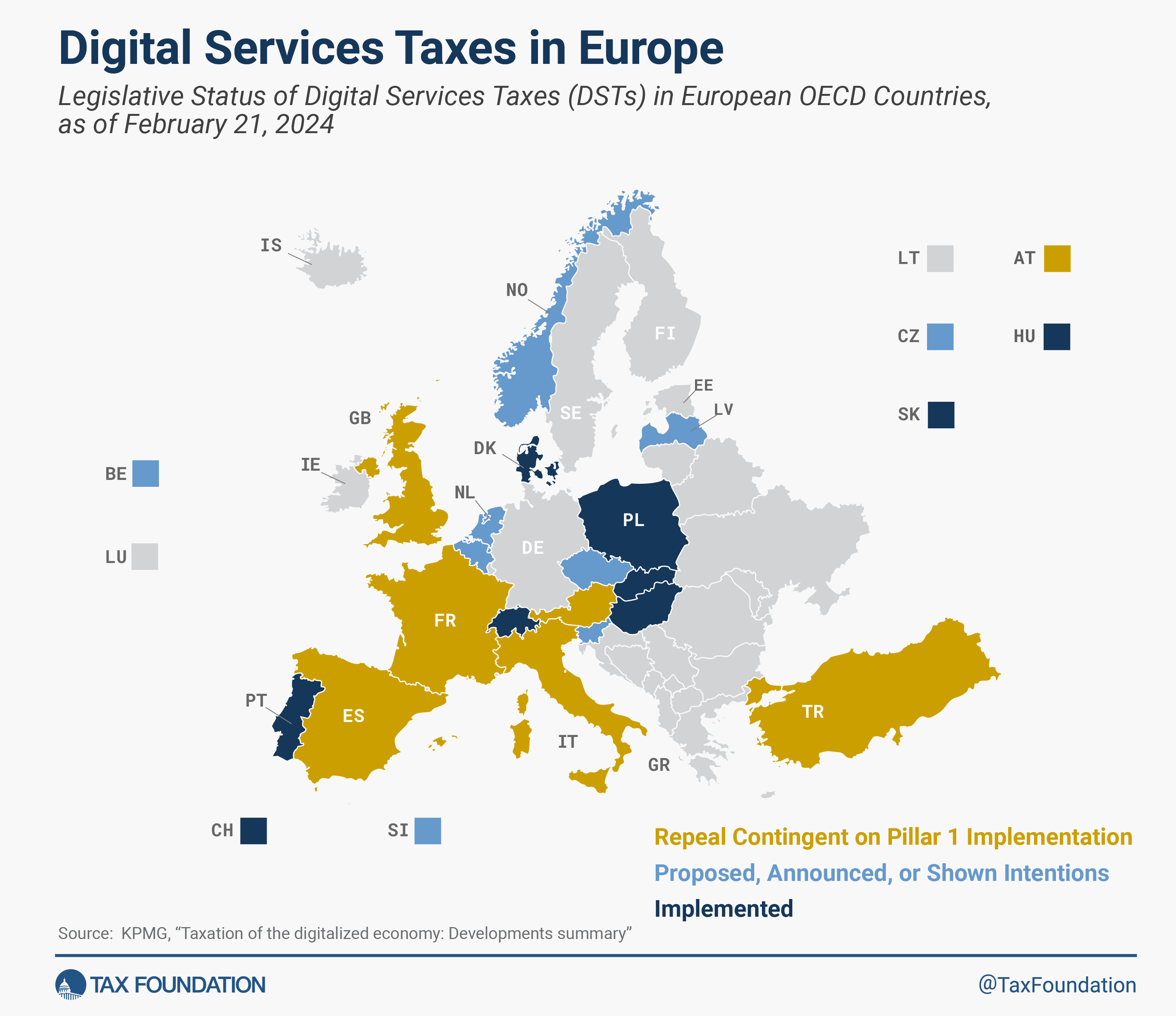

Today, those complexities and uncertainties are still present, and whether Pillar One will eliminate digital services taxes and other relevant unilateral measures is still unclear.

The draft multilateral tax treaty under Pillar One, Amount A would rearrange the rights to tax the largest multinational companies’ profits. According to the OECD, taxing rights on about $200 billion in profits would be shifted to jurisdictions different from where the profits are currently being taxed. Due to tax differences in current vs. proposed jurisdictions, the changes would lead to a tax increase between $17 billion and $32 billion, based on 2021 data. This tax increase will impact many large companies, but only certain countries will receive additional revenue.

Specifically, the OECD’s analysis points to revenue gains in low- and middle-income countries and losses primarily in jurisdictions often referred to as tax havens.[2]

There has been continued bipartisan support for eliminating DSTs because they discriminate against U.S.-based companies. However, even with Amount A, countries may keep their DSTs.

On the other hand, if Pillar One, Amount A is not agreed to, then DSTs will likely become even more common around the world. And the United Nations will likely seek to fill the gap in multilateral tax policymaking. Because the UN relies on a one-country-one-vote approach to decisions (while the OECD has aimed for consensus), and it has yet to set a clear policy agenda, its policy designs are difficult to predict.

Work done by members of this committee on H.R. 3665 shows the desire for stronger tools to retaliate against extraterritorial and discriminatory foreign taxes.[3] Members should be cautious about using such tools. The threat of a new tax and trade war with Europe is very real, with economic damages on both sides of the Atlantic. Retaliation does not guarantee the U.S.’s desired outcome—namely, the removal of discriminatory policies—but it will bring additional escalation and economic damages. The EU can put tariffs on U.S. exports just as easily as the U.S. can put tariffs on French wine.

Where there are opportunities to resolve disputes using either multilateral tax negotiations or leaning on the World Trade Organization, policymakers should prioritize those opportunities over retaliation.

My testimony will cover key items for policymakers to consider in the design of Pillar One, Amount A and the current situation for digital services taxes.

Digital Services Taxes

Since 2018, many countries have sought to use novel tools to tax the profits of large multinational companies in the digital sector. The most common of these tools has been the digital services tax. These policies usually apply a single-digit tax rate to the revenues of a large company.

These policies are problematic for two reasons.

First, they are discriminatory. One common model is to set a revenue threshold high enough that most businesses impacted by the tax are companies not headquartered in the implementing jurisdiction (most commonly, U.S.-based companies). Additionally, the policies are targeted at specific business lines (such as online streaming services, digital advertising, and the sale of user data). This violates the principle of neutrality.

Second, they tax companies on gross revenues rather than income. This means that the tax will be owed regardless of whether a particular digital service is profitable in the jurisdiction levying the tax. Gross revenue taxation can also create tax pyramidingTax pyramiding occurs when the same final good or service is taxed multiple times along the production process. This yields vastly different effective tax rates depending on the length of the supply chain and disproportionately harms low-margin firms. Gross receipts taxes are a prime example of tax pyramiding in action.

as costs for digital services taxes may hit a company’s value chain at multiple points without the opportunity for recouping those costs.[4]

Because the United States is home to most of the companies impacted by these DSTs, U.S. lawmakers have consistently argued against the policies, including very recently in a letter from Senate Finance Chairman Sen. Wyden (D-OR) and Ranking Member Sen. Crapo (R-ID) about Canada’s proposed DST.[5]

One clear goal for U.S. policymakers has been to eliminate DSTs either through a multilateral agreement or through trade threats and a potential trade war. In 2020, the Trump administration announced 25 percent tariffs on $1.3 billion worth of trade with the European Union in response to the French DST.[6] These tariffs had a delayed implementation date and are currently still on hold.

Canada is the most recent entrant into the DST scene with a 3 percent rate on revenues from online marketplaces, social media platforms, sale and licensing of user data, and online ads with at least EUR 750 million (USD 812 million) in total annual worldwide revenues and Canadian revenues of CAD 20 million (USD 14.7 million).

The tax would be calculated on Canadian in-scope revenues for any calendar year that exceeds CAD 20 million. The policy has been adopted but has not yet been implemented.

Design of Pillar One, Amount A

Partially in response to DSTs, countries have been negotiating at the OECD on a multilateral solution.

Pillar One, Amount A changes the rules for where companies pay taxes. Currently, companies generally pay taxes on their profits based on where those profits are generated by employees, laboratories, manufacturing, or distribution facilities. Amount A entails a series of formulas to shift a portion of taxable profits away from jurisdictions where profits are booked currently—that is, where they are produced—and move them to jurisdictions where sales are made to final consumers.

The rules would initially impact companies with global revenues above EUR 20 billion (USD 21.6 billion at recent exchange rates) and profitability above a 10 percent margin. The revenue threshold would be cut in half after a review in the seventh year of the policy.

The rules take 25 percent of profits above a 10 percent margin and allocate that share to jurisdictions according to the share of sales in jurisdictions around the world.

The rules include approaches for identifying final consumers even when a company is selling to another business in a long supply chain. The rules also allow companies to use macroeconomic data on final consumption expenditure to allocate taxable profits when the location of final customers cannot be identified.

The rules define both where taxable profits are moved to, and where taxable profits are shifted from.

The jurisdictions that will give up taxable profits are split into different tiers according to the different ratios of profits to depreciationDepreciation is a measurement of the “useful life” of a business asset, such as machinery or a factory, to determine the multiyear period over which the cost of that asset can be deducted from taxable income. Instead of allowing businesses to deduct the cost of investments immediately (i.e., full expensing), depreciation requires deductions to be taken over time, reducing their value and discouraging investment.

and payroll. This approach ensures that jurisdictions with the highest levels of profitability (compared to depreciation and payroll) will be the first to give up taxable profits to the benefit of jurisdictions where final sales are made.

These rules are incredibly complex, and it is difficult to see how they can be complied with or administered without much uncertainty and disputes over implementation.

Pillar One, Amount A Impacts

The U.S. tax baseThe tax base is the total amount of income, property, assets, consumption, transactions, or other economic activity subject to taxation by a tax authority. A narrow tax base is non-neutral and inefficient. A broad tax base reduces tax administration costs and allows more revenue to be raised at lower rates.

would be impacted directly by these rules. U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has previously written that she believes Amount A would be roughly revenue neutral for the U.S.[7] For this to be true, the U.S. would need to collect significant revenue from foreign companies or from U.S. companies that sell to U.S. customers from foreign offices. Also, Pillar Two, the global minimum tax, would need to be somewhat ineffective at changing the behavior of U.S. companies to put (or keep) valuable intellectual property in the U.S. rather than placing it offshore.

More recently, Sec. Yellen has said that “significant disagreements” make determining the fiscal impact difficult.[8]

Amount A creates clear winners and losers when it determines which jurisdictions get to tax the profits in scope. If a jurisdiction has a large market, then it will likely win out from the Amount A rules. If a jurisdiction has business entities with very high profit margins, then it will likely lose taxable profits.

The U.S. has both a large market and is home to many multinationals with high profit margins.

If Pillar One Amount A gets adopted, then it will coexist with the global minimum tax. The minimum tax will, over time, change where businesses locate their high-value assets, particularly intangible property.

By many accounts, U.S. companies will bear the brunt of Amount A. What that means for the U.S. tax base is less clear.

Currently, the U.S. runs a significant trade surplus in charges for the use of intellectual property (royalties). According to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, that surplus has averaged $76 billion per year from 2017 to 2022. The overall trade surplus in services was $2.3 billion in 2023.[9] Additionally, year-over-year growth in private fixed investment in intellectual property (IP) products has averaged 8.7 percent since the beginning of 2017.[10]

These data are indicative of the U.S.’s strong position for trading services, many of which (particularly intellectual property services) are high value and have high profit margins. The U.S. Treasury would likely raise less money from these companies exporting high-value services from a U.S. base if Amount A is adopted.

Furthermore, if Pillar Two works as intended (and the U.S. remains an attractive place to invest in IP), then new, valuable IP that stays in the U.S. and results in significant sales to foreign customers would further strengthen U.S. service exports and even potentially make the U.S. a net donor in the Amount A framework.

On the other hand, the U.S. may see some revenue benefits from Amount A. Some U.S.-headquartered companies that have modest profit margins within the U.S. have very high profit margins around the world (often due to IP that they hold in offshore jurisdictions). In some cases, the IP is also developed offshore. A decent share of those companies’ customers may be in the U.S. So, when the profits are moved to the customers’ location, the U.S. tax base for that company could grow because the most profitable jurisdictions (relative to depreciation and payroll) will be the ones giving up the tax base.

Policymakers should analyze these interactions. The difference-maker would be U.S. companies with high profit margins in foreign jurisdictions and a large portion of their sales made to U.S. customers. Even if those companies are paying tax to the U.S. via the inclusion of global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI), the rate difference between GILTI and the U.S. federal rate will increase tax revenue from those companies.

The Future of Pillar One, Amount A

Pillar One, Amount A has been negotiated by nearly 140 jurisdictions around the world, and it would require a multilateral treaty to be implemented.

This multilateral tax treaty has not yet been finalized for a couple of reasons. First, the U.S. Treasury wanted to get public input on the draft treaty. And second, several countries have expressed objections to the draft proposal.

Brazil, Colombia, and India object to several provisions, including one that suggests current taxes applied in market countries should reduce the new opportunity to tax profits allocated under Amount A. This is a question of double dipping. If a country already has the right to tax a business on its activity in a country by using withholdingWithholding is the income an employer takes out of an employee’s paycheck and remits to the federal, state, and/or local government. It is calculated based on the amount of income earned, the taxpayer’s filing status, the number of allowances claimed, and any additional amount of the employee requests.

taxes, and Amount A would allocate new taxing rights, should the new right be a gross allocation or a net allocation? In my view, Amount A should not duplicate existing taxation that is happening in market jurisdictions.

Brazil, Colombia, and India seem to agree that Amount A should be a gross allocation with no offset for existing taxes owed. Other countries appear to be aiming for a net allocation where the Amount A taxing right is reduced by existing rights to tax in a market jurisdiction.

As of last October, these differences had not yet been resolved.

The draft treaty has a scoring system that determines when the treaty has achieved enough signatories to be implemented.[11] The key threshold for several provisions is 600 points, and 999 points are available. The United States has been attributed 486 points. This means that the 600-point threshold cannot be achieved without the United States.

Therefore, the question of U.S. ratification will determine the treaty’s future.

The Fate of Digital Services Taxes

A major justification for the negotiations leading to Pillar One, Amount A was the possibility of eliminating DSTs. However, even with Amount A, countries may keep their DSTs anyway.

One key element of the draft treaty released last fall is Annex A, where one can find a list of policies that will be removed once the treaty is adopted. Included in that list are the DSTs of eight countries.[12] The list is not fully inclusive of all discriminatory digital tax policies. But the draft treaty also eliminates the Amount A allocation to countries that do not remove policies that fit within the draft treaty’s definition of DSTs and relevant similar measures:[13]

- The tax is driven by the location of customers or users.

- It is generally a tax on foreign businesses.

- It is not a tax on income and is beyond agreements to avoid double taxationDouble taxation is when taxes are paid twice on the same dollar of income, regardless of whether that’s corporate or individual income.

.

The incentive to remove a DST other than those already specified will likely depend on whether a country sees a better tax revenue outcome from Pillar One, Amount A. In turn, those revenue numbers will depend on how the rest of Amount A gets negotiated.

Also, it seems unlikely that these principles will result in “all” DSTs being removed as agreed in October 2021.[14] There is room for governments to work around the principles above. A DST could potentially get past the second principle by applying to both domestic and foreign businesses in a somewhat balanced way.

Five European countries have an agreement with the United States to reduce tax payments under Pillar One, Amount A in connection with the amount of taxes paid under a DST. This agreement is time-limited and will expire on June 30, 2024, unless extended further.[15]

Conclusion

With Pillar One, Amount A, very little is truly certain. It is uncertain whether a robust system for allocating profits is achievable. And even if it is, it may not result in the removal of all DSTs. The limited list and the option to retain such policies run contrary to the goals set out on a bipartisan basis by members of Congress. One thing that is more certain, however, is that if a multilateral solution to remove the DSTs is not agreed to, then DSTs will continue to spread and mutate with negative impacts on some of the most innovative companies in the world.

Multilateralism is better than multiple rounds of a tax and trade war. As other countries lean toward unilateral approaches, though, it is worth recalling the unilateral U.S. approach to redefine where companies pay taxes, namely the border-adjusted tax proposal from 2016.[16]

As mentioned, the UN is building its own role in multilateral tax negotiations. In that forum, the United States and likeminded nations will likely have less leverage due to the procedural differences from the OECD.

In any case, the mess of multilateral tax policy will likely continue for some time.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

[1] Daniel Bunn, “Response to OECD Public Consultation Document: Secretariat Proposal for a ‘Unified Approach’ under Pillar One,” Tax Foundation, Nov. 11, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/global/response-to-oecd-public-consultation-document-secretariat-proposal-for-a-unified-approach-under-pillar-one/.

[2] OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit ShiftingProfit shifting is when multinational companies reduce their tax burden by moving the location of their profits from high-tax countries to low-tax jurisdictions and tax havens.

Project, “International tax reform: Multilateral Convention to Implement Amount A of Pillar One,” October 2023, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/multilateral-convention-to-implement-amount-a-of-pillar-one.htm.

[3] Defending American Jobs and Investment Act, H.R. 3665, 118th Congress (2023), https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/3665.

[4] Tax Foundation, “Tax Pyramiding,” TaxEDU, https://taxfoundation.org/taxedu/glossary/tax-pyramiding/.

[5] Letter to Ambassador Tai from Senate Finance Committee Chairman and Ranking Member, Oct. 10, 2023, https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/20231010wydencrapolettertoustroncanadadst.pdf

[6] Daniel Bunn, “Digital Taxes, Meet Handbag Tariffs,” Tax Foundation, Jul. 10, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/blog/us-french-tariffs/.

[7] Letter to Senator Mike Crapo from Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Jun. 4, 2021, https://mnetax.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Yellen_letter_to_Crapo_on_OECD_tax_negotiations920.pdf.

[8] Isabel Gottlieb, “Global Deal Disputes Prevent Exact Revenue Estimate, Yellen Says,” Bloomberg Tax, Mar. 10, 2023, https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report-international/global-deal-disputes-prevent-exact-revenue-estimate-yellen-says.

[9] “International Transactions, International Services, and International Investment Position Tables, Table 2.1 U.S. Trade in Services by Type of Service,” Bureau of Economic Analysis, data last revised Jul. 6, 2023, https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/?reqid=62&step=9&isuri=1&6210=4#eyJhcHBpZCI6NjIsInN0ZXBzIjpbMSw5LDZdLCJkYXRhIjpbWyJQcm9kdWN0IiwiNCJdLFsiVGFibGVMaXN0IiwiMjQ1Il1dfQ==. The trade surplus could be much higher, however. In recent years, BEA data and Eurostat data have disagreed on the trade of intellectual property services; Eurostat has shown much higher trade surpluses for the U.S. with European Union Member States than the Bureau of Economic Analysis. For example, the U.S. royalties trade surplus with Ireland was nearly €100 billion ($110 billion) in 2022, according to “Balance of payments by country – quarterly data (BPM6),” Eurostat, data last updated Oct. 13, 2023, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/bop_c6_q__custom_8779444/default/table.

[10] “National Income and Product Accounts, Table 5.6.6. Real Private Fixed Investment in Intellectual Property Products by Type, Chained Dollars,” Bureau of Economic Analysis, data last revised Sep. 29, 2023.

[11] OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, “The Multilateral Convention to Implement Amount A of Pillar One,” Table 2. Annex I, October 2023, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/multilateral-convention-to-implement-amount-a-of-pillar-one.pdf#page=212.

[12] OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, “The Multilateral Convention to Implement Amount A of Pillar One,” Annex A, October 2023, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/multilateral-convention-to-implement-amount-a-of-pillar-one.pdf#page=91.

[13] OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, “The Multilateral Convention to Implement Amount A of Pillar One,” Part VI – Treatment of Specific Measures Enacted by Parties, October 2023, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/multilateral-convention-to-implement-amount-a-of-pillar-one.pdf#page=77

[14] OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project, “Statement on a Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy,” Oct. 8, 2021, https://www.oecd.org/tax/beps/statement-on-a-two-pillar-solution-to-address-the-tax-challenges-arising-from-the-digitalisation-of-the-economy-october-2021.pdf#page=3.

[15] U.S. Treasury, “The United States, Austria, France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom Announce Extension of Agreement on the Transition from Existing Digital Services Taxes to New Multilateral Solution Agreed by the G20/OECD Inclusive Framework,” Feb. 15, 2024, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy2098.

[16] Kyle Pomerleau, “Understanding the House GOP’s Border Adjustment,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 15, 2017, https://taxfoundation.org/research/all/federal/understanding-house-gop-border-adjustment/.

Share

[ad_2]

Source link