[ad_1]

I noted a new report from the Resolution Foundation on Monday. In that report, that think tank suggested that maybe 30% of all households in the UK had savings of less than £1,000 available to them. The solution that the Resolution Foundation suggested was, quite extraordinarily, that those households should be forced to save more. They appeared to never consider the possibility that the reason why these households have such low savings is that they already have almost no capacity to save because their costs of living absorb all their available earnings.

Standing back, there is a particularly perverse aspect to this recommendation. Only a few months ago, I highlighted another perverse report from the Resolution Foundation in which they suggested that the government should run surpluses in most years. This, they suggested, would then provide the government with the capacity to run deficits if they might ever be required. In the process, they revealed a complete lack of understanding of macroeconomics. They obviously think this to be similar to the economics of a household. Nothing could be further from the truth. Governments can create money to manage deficit spending, but households cannot. This straightforward fact was either not known to or was assumed away by the Resolution Foundation. What they did, however, also reveal was their lack of awareness of one of the most basic analytical tools within macroeconomics, which is sectoral balance analysis.

Sectoral balance analysis assumes that the economy is made up of just four sectors. These are:

- The household sector

- The corporate sector

- The government sector

- The overseas sector, i.e. the transactions that those normally resident outside the UK undertake in sterling.

Sectoral balances in an economy like that within the UK seek to highlight the net savings and borrowings that take place between the sectors.

The assumption implicit in this analysis is quite straightforward. It is assumed that if some sectors are in surplus in a period, meaning that they save, then it must follow that other sectors must be in deficit, i.e. they borrow. This is the necessary consequence of the infallible logic implicit within double-entry bookkeeping, which is that every action has a reaction, requiring as a result that any saver must, by definition, create a borrower, even if that is only a bank.

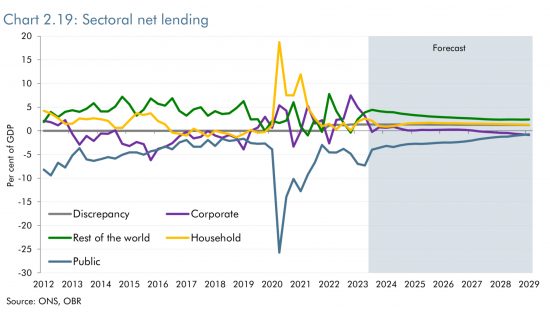

The evidence of recent years is that households are not very good at saving, except during the Covid crisis. By and large, they also seem to have spent the money they saved then. The latest forecast for the sectoral balances, as prepared in November 2023 by the Office for Budget Responsibility, as noted below, shows that they do not forecast any change to the modest net savings now made by households for some time to come.

I also note from that forecast that the OBR does not expect the corporate sector to borrow for some time to come, and then, when it does, it will do so only very modestly. Candidly, I think that an optimistic projection by the OBR: given the stagnant UK economy that is forecast for years to come there is no reason for business to invest much.

It would also seem that the Office for Budget Responsibility is, as ever, wildly optimistic about the probability that the government will cut its borrowing over coming years. This is a consistent feature of their forecasts, almost all of which have always been decidedly over-optimistic in this regard.

If, however, as they do forecast, the government does cut its borrowing, and given that neither households nor businesses are much inclined to borrow, the inevitable net consequence is that the overseas sector must, in net terms, save less in the UK than it has done for a long time. This might happen, with Brexit finally creating this consequence, but there is no evidence as yet to suggest that this is likely.

Then, though, let me presume that what the Resolution Foundation wants occurs and that households save more and the government moves into surplus, as they would like, whilst the corporate sector remains broadly neutral. With those three sectors all then moving into positive territory the inevitable requirement would be that the overseas sector would then have to borrow sterling rather than save in it, as has been its accustomed behaviour.

I accept that this might be a consequence of the government borrowing less when much of the overseas sector is saved in gilts. That, though, seems unlikely. There are, after all, very many good reasons why overseas governments do want to hold sterling reserves, not least to support trade but also as part of the balances that underpin the IMF’s special drawing rights and other reserve balances. The UK also remains an attractive place for many to save, given the relative financial stability that it still supplies for some who require it. In summary, I simply cannot see the overseas sector moving into negative territory, which, as the chart shows, would be exceptionally unusual in the current era.

In that case, does the Resolution Foundation’s suggestion that both households and the government should save more make any sense at all? The obvious answer is that it does not.

Think tanks are very good at suggesting that governments should do joined-up thinking. It looks to me as though the Resolution Foundation might need to do the same. It might also need to sharpen up its understanding of macroeconomics. It might be a little more credible if it did so.

[ad_2]

Source link