[ad_1]

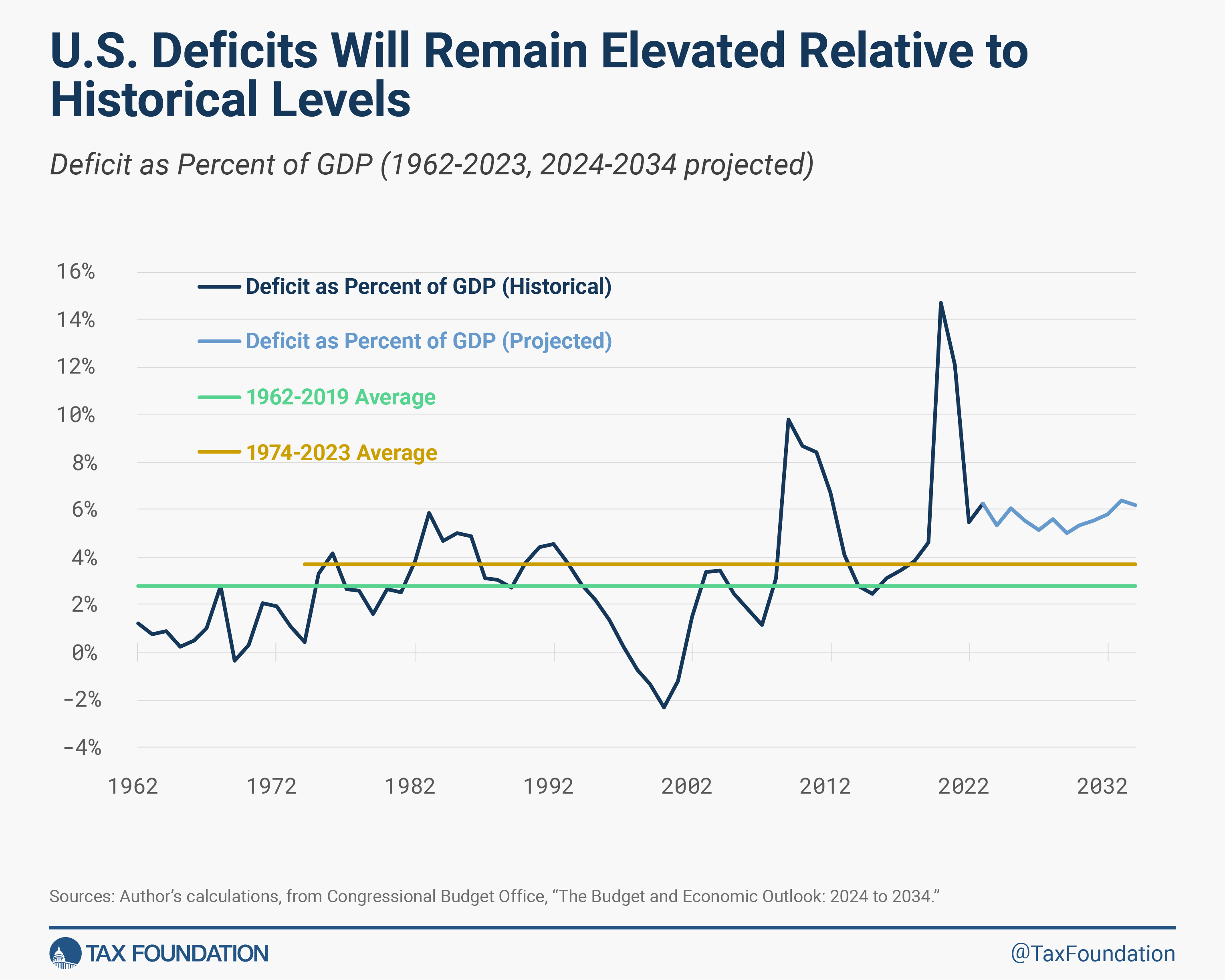

Last week, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released an updated Budget and Economic Outlook. The report (released annually) presents the agency’s current projections of major fiscal and economic trends for the coming decade and beyond. While aspects of the country’s fiscal picture look better compared to previous iterations, the overall outlook is still concerning. The CBO projects deficits will be higher than historical levels, largely due to growth in mandatory spending programs like Social Security and Medicare. And while some recent legislation has reduced the deficit, the Inflation Reduction Act is proving to be more expensive than originally promised.

Big Picture Looks Grim

Both spending and revenue are projected to be elevated above historical levels. Over the previous 50 years (from 1974 to 2023), total outlays averaged 21.0 percent of GDP, while total revenue averaged 17.3 percent of GDP. However, over the next 11 years (from 2024 to 2034), both numbers will be elevated above their averages. From 2024 to 2034, total outlays are projected to average 23.4 percent of GDP, while total revenues are projected to average only 17.7 percent of GDP. The larger increase in outlays shows how spending is the primary driver of further rising deficits.

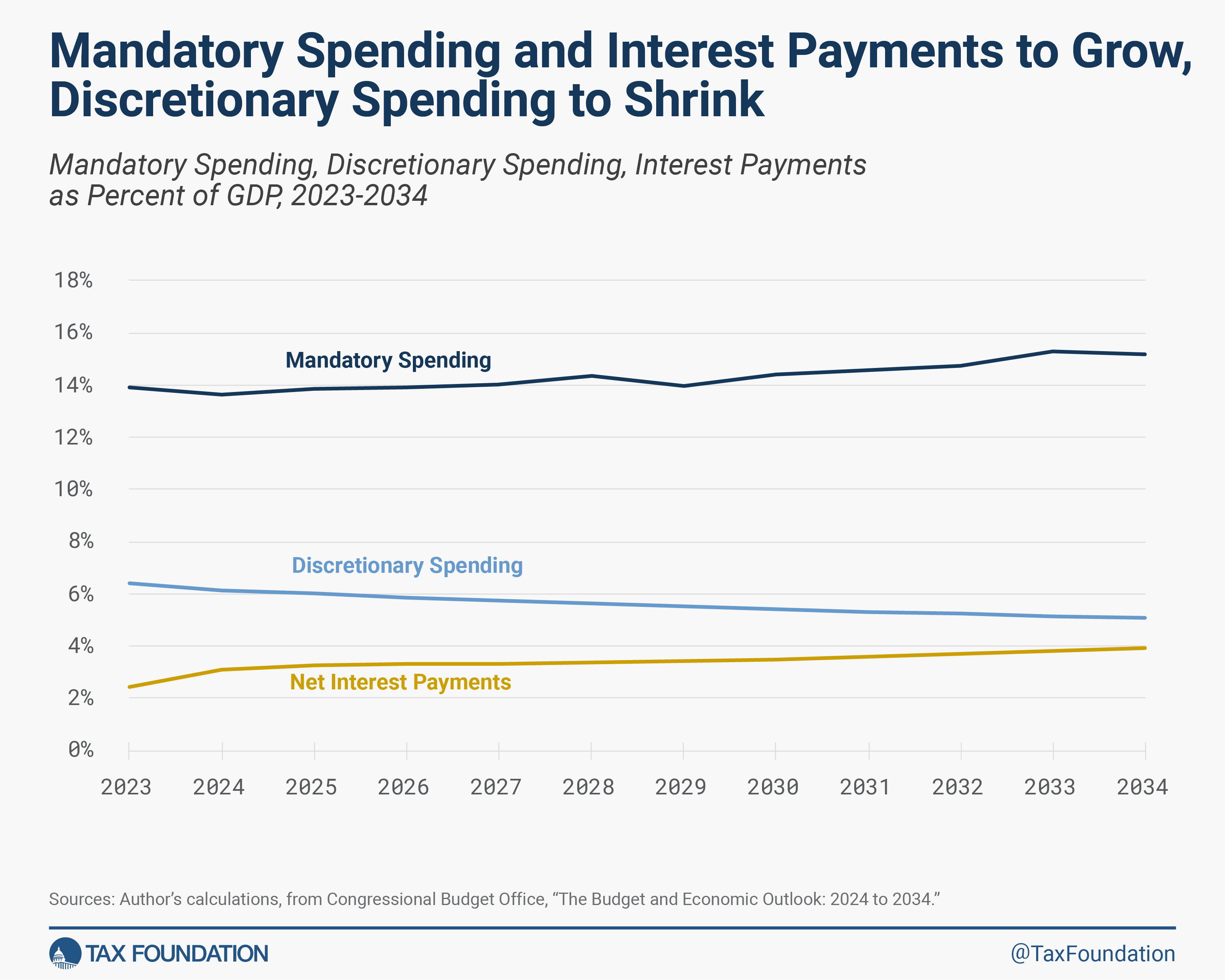

Increased outlays are primarily to blame for higher deficits going forward, particularly the growth in mandatory spending programs, including Social Security and Medicare, and rising interest on the debt. From 2024 to 2034, mandatory spending will grow from 13.6 percent of GDP to 15.2 percent of GDP, while discretionary spending will decline from 6.2 percent of GDP to just 5.1 percent of GDP. The remaining increase in outlays is due to a historic increase in interest payments, which go from 3.1 percent of GDP in 2024 (exceeding the defense budget for the first time in records going back to 1940) to a new record high of 3.2 percent in 2025, before rising higher to 3.9 percent in 2034.

In effect, rising interest costs and mandatory spending on major entitlement programs are crowding out spending on core government functions in the discretionary budget, including defense, law enforcement, and infrastructure.

Progress Made on Some Points, Not Enough on Others

The CBO reduced its projections of the cumulative deficit from 2024-2033 relative to the same period in its last estimate as of May 2023, from $20.3 trillion to $18.9 trillion—a net reduction of $1.4 trillion. Legislative changes collectively reduced the projected cumulative deficit by $2.6 trillion over that period, with the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 (FRA) responsible for a large share of that difference. The vast majority of that effect comes from reducing discretionary spending, which was already on a downward trajectory as a share of the economy prior to the FRA, while growth in mandatory spending was essentially untouched.

Impact of Recent Legislation and Coming Changes

The new outlook also shed some light on the InflationInflation is when the general price of goods and services increases across the economy, reducing the purchasing power of a currency and the value of certain assets. The same paycheck covers less goods, services, and bills. It is sometimes referred to as a “hidden tax,” as it leaves taxpayers less well-off due to higher costs and “bracket creep,” while increasing the government’s spending power.

Reduction Act of 2022. The report estimates energy-related taxA tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by local, state, and national governments from individuals or businesses to cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

provisions will increase deficits by $427.7 billion more than previously projected between 2024 and 2033, offsetting some of the savings from the FRA. While several factors contribute to this change, an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rule change has the largest effect. In April 2023, the EPA proposed stricter vehicle emissions standards starting in 2027. This rule change reduces revenues through two channels: it increases the adoption of electric vehicles (and thus usage of the clean vehicle tax credits), and it decreases gas taxA gas tax is commonly used to describe the variety of taxes levied on gasoline at both the federal and state levels, to provide funds for highway repair and maintenance, as well as for other government infrastructure projects. These taxes are levied in a few ways, including per-gallon excise taxes, excise taxes imposed on wholesalers, and general sales taxes that apply to the purchase of gasoline.

revenue (as it will reduce the usage of gas-powered cars).

Initially, the CBO scored the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) as a deficit-reducing policy, on net reducing the deficit by $90 billion between 2022 and 2031 plus about $200 billion in increased revenues from increased IRS enforcement. But these new cost estimates make it clear that the IRA will end up increasing the deficit. Now, based on CBO’s latest estimates, the IRA credits appear to cost approximately $786 billion over the new budget window (2024-2033), indicating the IRA legislation in total increases deficits by about $300 billion from 2024 to 2033, or $562 billion excluding the effects of IRS enforcement. Note this is a rough estimate, as it mixes two CBO baselines, but it shows the need for the CBO and the Joint Committee on Taxation to provide transparency and a new estimate of the IRA’s budgetary impact.

Contrarily, the upcoming expiration of much of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is behind the projected increase in tax revenue as a share of GDP later in the coming decade. Many of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s expiring provisions ought to be made permanent. At the same time, though, they ought to be accompanied by either tax revenue offsets or spending reductions to prevent permanence from raising the already-rising debt. It appears from the CBO’s latest analysis that capping or repealing many of the IRA credits would offset a substantial portion of the cost of extending key parts of the TCJA.

Conclusion

While the recent report is not all doom and gloom, it does show a still-concerning long-term fiscal picture. There are three main factors that go into the deficit: spending, revenue, and economic growth. As policymakers (hopefully) move to reduce the deficit going forward, they must contend with the primary driver of the deficit: mandatory spending on Social Security and Medicare. Increasing revenue may be part of the solution as well, but it should be done in a manner that maintains or enhances economic growth. After all, federal tax revenue collections and the spending that it supports are a derivative of the health and size of the U.S. economy.

Stay informed on the tax policies impacting you.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

Share

[ad_2]

Source link